It’s a new year! And it’s time to bet involved in your child’s education.

Sure, we all check report cards, and most of show up for conferences, but that’s not nearly enough. We’ve accepted the notion that decisions about education should be made by “the experts.” That might be a good idea if there actually were experts and if those experts knew precisely what was best for your child. You should be the expert when it comes to each of your children.

How much do know about what your student is experiencing in his or her schooling? Does your child enjoy school? Can you tell how well he or she is learning? How much of what is being presented is pertinent to actual education?

It’s the nature of the beast—”weapons of mass education,” so to speak—one curriculum, one teacher, one assessment system for many, many students. Worse yet, much or all of it is now online. Under the best of circumstances, students, even in the earliest grades, must learn on their own. A teacher presents information, assigns homework, and makes an assessment. This happens several times a day, each day students are in school, for twelve or more years of their lives. Some students flourish, but most do not.

When you think about the commitment of your child’s time, you must realize it’s enormous. Think, too, about the consequences for failure, since a relatively small number of students prosper. That’s the best reason to get involved in your child’s education, but there are others.

What about the Curriculum in Your District: Meaningful? Effective? Far Out?

These are not easy questions to answer unless you’ve spent some time delving into the curriculum. But, why wouldn’t you? All the information and ideas that your child is absorbing are coming from relatively limited sources. One of the biggest, especially for young children, is the school.

Is the curriculum meaningful in terms of your child’s development? Does a six-year-old child need instruction in social and emotional learning, or do they need more time in reading and math?

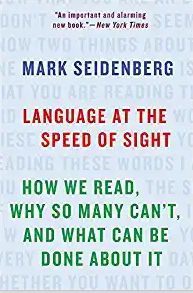

Of course, at SoundEnglish, the critical starting point is reading. Do you know how it is taught in your district, and is it benefitting your child? Researchers have spent vast amounts of time and money examining methods and settling “reading science.” Most schools, however, are paying little attention, as we have pointed out.

Let’s consider another basic discipline—math. The “new math” derived from Common Core is particularly interesting. Rather than elaborate, I’ll encourage you to look at this video that was posted in April of 2019. Is this the way you want your child to learn math?

New and Different Doesn’t Make It Better than Memorization

So much of what’s described as “modern methods” flies in the face of common sense. For some time, educators have decried two tools that teachers have used for generations: memorization and testing. Let’s talk about these.

Teachers complain that memorization is boring. That’s true, but why? It’s because the key to memorization is repetition. Is it boring for teachers and students? Surely! But that doesn’t make something else better. Memorization is still the most efficient way to teach essential systems like numbers and letters. That’s why we have all learned and taught letters and numbers with songs and rhymes.

Unfortunately, we don’t have that simple elegance available for learning basic math operations (addition, subtraction, etc.) or for developing phonemic awareness in reading. These are skills critical to students’ progress throughout their education. We shouldn’t be tampering with them, but we have been for years. We certainly shouldn’t be suggesting that memorization of simple facts is not helpful because it doesn’t lay out the whole of the discipline for the student, as suggested in this The Atlantic article.

How are your children progressing? Are they reading at or beyond grade level? How did the do on their last math test? And speaking of testing…

Get Involved in Your Child’s Education Testing?

The war against memorization has been going on for years, but objections to testing are a more recent development, probably within the past 10 years. As school systems developed their classes along national standards, the logical impulse was to test the students to confirm whether the standards were achieved. This has become a problem.

Why is it a problem? I’m told by teachers that they find it constraining to have to “teach to the test.” That’s hard for me to understand, since the test is about the standards, right? Once the standards are established, why wouldn’t you teach to the test? If the standards say that the average first grader must be able to count to 100, wouldn’t you teach the child to count to 100? (Which would, of course, involve memorization.) Nonetheless, teachers continue to raise a host of arguments, such as those at Thought.com.

Another issue educators raise with testing is that it is unfair for a variety of reasons, such as cultural bias. Some students have more difficulty with testing than others. However, it would be important to determine if the difficulty is that the student has had trouble absorbing the content, rather than blame the test. Of course, this could logically circle back to the objection about teaching to the test.

And we are not just talking about those big standardized tests; the objection is to testing in general. According to Alfie Kohl in Psychology Today, tests are meaningless. Really? It’s common sense that a well-constructed test is the most direct and efficient way to check a student’s learning. It could be an excuse for failures in the system. Administrators and teachers will cite the methods rather than performance.

Of course, it can’t be the students’ performance. They can’t learn what the teacher hasn’t taught. Let’s put that differently, since some students will manage to learn no matter what, but they are the exception. Most students will learn what is taught effectively. Some will still struggle.

How will you know the difference if you don’t get involved in your child’s education?