Last month, I focused on the conclusions of reading scientists about what it takes to teach reading effectively. However, there’s more to the science of reading than meets the eye. You might want to know more about the science of reading.

The primary motivation for the decades-long “reading wars” was a difference of opinion about how children learn to read. No one doubts that learning oral language is a natural process. Thus, it was logical to assume that learning written language was similar. Somehow, this assumption, combined with an $8 billion dollar textbook industry, has reduced the literacy of at least two generations of students. The actual consequences may stretch to four or five generations.

Finally, scientists who specialized in reading research for years are weighing in. In fact, some of the studies date back to 1980. It was that year that Philip Gough and Michael Hillinger at the University of Texas at Austin published “Learning to Read: an Unnatural Act.”

6-Year-Olds Are Amazing Creatures!

The opening of the report is a stunning contradiction. They begin by singing the praises of the average 6-year-old, standing at the open school door for the first time. The researchers praised the child’s brain, his eyesight, and his hearing. Gough and Hillinger marveled at his vocabulary: he had learned four words for each day of his life. The researchers suggested he knew more than a dozen vowels and 30 consonants. “Yet for all his cognitive and linguistic talents, the child has one peculiar linguistic shortcoming: he cannot read a word.”

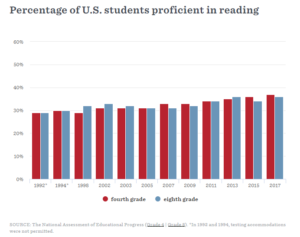

The saddest fact is that, despite first-, second-, and third-grade reading instruction, most fourth graders are not much better at reading than that 6-year-old. Okay, that’s an exaggeration. However, it is truthful to point out that about two-thirds of our fourth graders do not read with proficiency.

We’ve known about our failure for a long time. The graph shown here demonstrates the lack of progress in literacy for fourth- and eighth-graders since 1992. Emily Hanford, the senior education correspondent for APMReports.com, published “Hard Words: Why Aren’t Kids Being Taught to Read?” in September 2018. She correctly asserted that stakes for student are high. “Research shows that children who don’t learn to read by the end of third grade are likely to remain poor readers for the rest of their lives. They’re likely to fall behind in other academic areas, too.”

We’ve known about our failure for a long time. The graph shown here demonstrates the lack of progress in literacy for fourth- and eighth-graders since 1992. Emily Hanford, the senior education correspondent for APMReports.com, published “Hard Words: Why Aren’t Kids Being Taught to Read?” in September 2018. She correctly asserted that stakes for student are high. “Research shows that children who don’t learn to read by the end of third grade are likely to remain poor readers for the rest of their lives. They’re likely to fall behind in other academic areas, too.”

Hanford believes, as do many, that “scientific research has shown how children learn to read and how they should be taught. But many educators don’t know the science and, in some cases, actively resist it. As a result, millions of kids are being set up to fail.”

Why Can’t We Teach Reading Effectively?

It’s hard to say why this problem has persisted so long. The institution of the bi-annual NAEP tests shuld have motivated progress toward greater literacy by putting it in our faces every two years. They have failed.

The fact that American 15-year-olds take the PISA test every three years with 78 other nations hasn’t helped either. In the latest 2018 rankings, the U.S. was 13th in reading, bested by China (#1-4), Estonia, Canada, Finland, Ireland, Korea, Poland, Sweden, and New Zealand.

Hanford believes, as do many, that “scientific research has shown how children learn to read and how they should be taught. But many educators don’t know the science and, in some cases, actively resist it. As a result, millions of kids are being set up to fail.” In theory, it seems that science has actually resolved the question of how children should be taught to read. However, in reality, there still appear to be warring factions–the education schools, the publishers, and perhaps even teachers–who have continued the battle over the method. So far, science is losing and so are our children.

Balanced Literacy Is Not the Science of Reading

What is balanced literacy? It’s a great question without a solid answer. Some say it’s “a little bit of everything.” Others suggest that it is a compromise between the “two extremes:” phonics and whole-language. In case these are unfamiliar to you, I will summarize.

For several centuries in America, phonics instruction was the way to teach children to read. Phonics is a system of rules that teaches children how the symbols (letters) that make up words actually represent sounds. However, at some point in the last 100 years, the whole-language (also known as whole-word) method gradually replaced traditional phonics. This approach presumes children can learn written words as easily as they learned spoken words. This has proven to be abjectly false.

Balanced literacy includes features of both approaches. However, there was a report in the journal of the Association for Psychological Science summarizing the findings of three researchers. Scientists Anne Castles (Macquarie University), Kathleen Rastle (Royal Holloway University of London), and Kate Nation (University of Oxford) reported their conclusions as part of a thorough, evidence-based account of how children learn to read.

They summarized balanced literacy this way, “…what’s happened … in a lot of classrooms … a little bit of everything all at once. And what the research shows is that’s not actually what kids need. They don’t need a little bit of everything all at once.”

Reading Science Is Calling for Explicit Phonics Instruction

In the same article from the APS journal, scientist Anne Castles said, “Writing is a code for spoken language, and phonics provides instruction for children in how to crack that code. To acquire sophisticated literacy skills, for example, children must progress from identifying individual sounds to recognizing whole words. They must also be able to pull forth the meaning of different words quickly within a particular context in order to comprehend a whole unit of text, whether it’s a sentence, a paragraph, or an entire page.”

instruction for children in how to crack that code. To acquire sophisticated literacy skills, for example, children must progress from identifying individual sounds to recognizing whole words. They must also be able to pull forth the meaning of different words quickly within a particular context in order to comprehend a whole unit of text, whether it’s a sentence, a paragraph, or an entire page.”

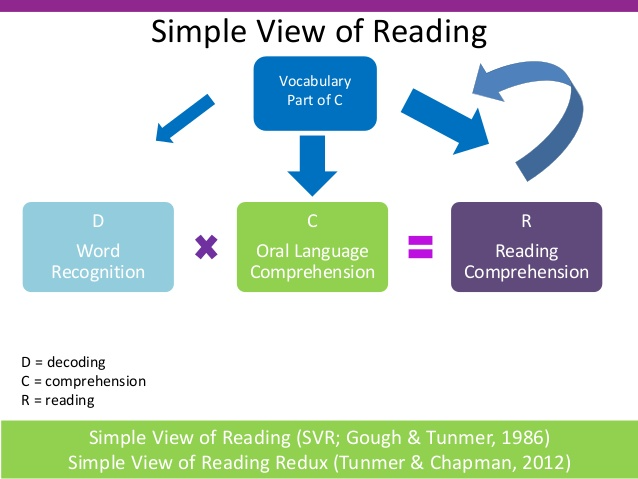

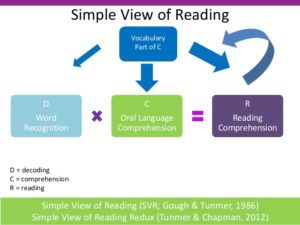

Reading scientists embrace “the simple view of reading.” Emily Hanford described the simple view of reading for EducationWeek:

“So the Simple View of Reading is a model that is now been backed up by lots and lots more research. It has a solid scientific base behind it. It essentially says, reading comprehension is the product of your language comprehension—the words you know how to say, the words you can hear—and your decoding ability. So if you multiply those two things together, you get reading comprehension.”

Hanford believes the message from science is clear. Systematic, explicit phonics instruction is what is needed to make our children readers. Unfortunately, that is not what teachers are learning in their training. It is also not what is happening in the schools.

Hopefully, someday soon, we will change that.