How much do you know about reading science? Most people don’t know it exists. It’s a relatively new field of study. Frankly, it’s late to the party, and the party’s been in full swing for a long time.

You may or may not know that our educational institutions have been adjusting reading methodology for decades. Previous to the twentieth century, the teaching of reading was primarily through phonics instruction. In the last century, however, we instituted new theories of teaching reading. The available evidence indicates that the “new” methods are not particularly effective. Thus, a few decades ago, the “reading wars” began.

Reading Wars Instead of Reading Science

In 2018, researchers Anne Castles, Kathleen Rastle, and Kate Nation published their study at sagepub.com. They summed up the situation this way: “For several decades, the ‘reading wars’ have waged between teachers, parents, and policymakers who champion a phonics-based approach (teaching children the sounds that letters make) and those who support a “whole-language” approach (focused on children discovering meaning in a literacy-rich environment).” Researcher James S. Kim suggests in a piece published in 2008 that the reading wars actually go back more than 200 years to Horace Mann and the Massachusetts Board of Education.

The justification for phonics-based reading instruction was that our letters are a code for spoken sounds. Once children crack the code, they can learn written words quickly and become proficient readers. A good analogy would be building a wall brick by brick. It can be tedious, and it takes a while, but the result is accurate and durable.

The opposing view—whole-language—takes the position that children can learn to read the way they learned to speak—in whole words. It’s an interesting theory and has been the staple of reading instruction for more than half of the last century. Those who favor it believe in kids deriving words from context and don’t believe it’s useful to learn to sound out unfamiliar words

What Have We Learned So Far?

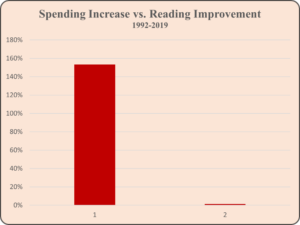

Much effort has gone into determining what is best for our students. The government empowered the National Assessment of Educational Progress in 1969. Since 1990, the organization has been testing students in grades 4, 8, and 12 in reading and math every two years. Over the course of the last 32 years, we would logically expect that all this attention would produce gains in reading. However, we would be wrong. You can find the latest “report card” from NAEP and see for yourself. In 1990, the reading score for fourth graders was 217; in 2019, it was 220, a insignificant increase. Plus, the score was down from 2017.

According to Michael Petrilli, a fellow at Stanford’s Hoover Institution and the editor of Education Next, “The National Reading Panel declared in 1999 that students needed to be taught to read explicitly, including purposeful attention to phonics and phonemic awareness.” Congress responded in 2002 by creating the “Reading First” initiative as a feature of No Child Left Behind. Unfortunately, the program prompted the investigation of a financial scandal in the Department of Education. Consequently, it never really got off the ground.

We Lost This Battle in the Reading War

Petrilli’s piece goes on to explain that the proposed program was “polarizing among education-publishing oligarchs and, of course, infuriating to the ‘whole language’ crowd…and almost immediately, many popular publishers starting dressing the now-suspect whole-language wolf in ‘balanced literacy’ clothing.”

Thus, it continues, and most of our children do not learn to read well. It makes you wonder why we keep going on this way. It may have something to do with the fact that the five largest textbook publishers are making upwards of $12 billion each year. They are described in this infographic as a cartel. Yes, that’s an association of manufacturers or suppliers who work together to keep prices high and minimize competition.

What Does Reading Science Say?

First, reading science demands explicit instruction for the teaching of reading. Explicit instruction is a methodology specifically for those with learning disabilities. It employs instruction that is direct, structured, and specific. It leaves nothing open to interpretation. Explicit instruction prescribes both the content of lessons and the method of presentation to maximize the benefit to the student. In general, there are three steps to teaching a lesson with explicit instruction:

- the teacher demonstrates by doing the task to be learned;

- the teacher guides the students through doing the task themselves; and

- the students have independent practice to reinforce what has been learned.

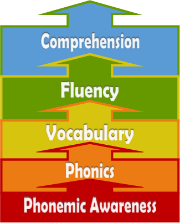

Second, reading science specifies that there are five foundational skills required for reading proficiency. Therefore, for any teaching method to be effective, it must focus on the development of each of the foundational skills. These are:

- phonemic awareness—the ability to hear individual speech sounds (phonemes) in spoken words

- phonics—the study of the predictable connections between letters in written words and the speech sounds they represent

- vocabulary—the number and variety of words a person understands and uses

- fluency—the ability to move through language with ease and accuracy, and

- comprehension—the capacity for understanding fully.

Follow the Science

That’s an edict we’ve heard repeated for years. It is proscribed for climate change; it is demanded for the pandemic. However, it is almost universally ignored for teaching our children to read. Even after more than 30 years of static test results, we plod on. After three decades of knowing that two-thirds of our students never become fluent readers, we cling to mediocrity.

Years ago, it may have been logical to assume that reading, like speaking, would come naturally. However, now we know for a fact that it does not. It’s time for a change.