I am convinced that facility with language is the key to reading, and, ultimately, to learning. It seems obvious. What is not obvious is why some students acquire this facility with relative ease while others struggle and often never catch up. The difference may be 30 million words, more or less.

Thirty Million Words was written by Dr. Dana Suskind and appeared in 2015. Simply put, the book asserts that the key to academic achievement is early language development from birth to three years. At first, this may be difficult to accept. Nevertheless, Suskind demonstrates that low-income children will hear as many as 30 million words less than wealthier children during those critical years. So what?

Is the 30 Million Words Gap Fact or Fiction?

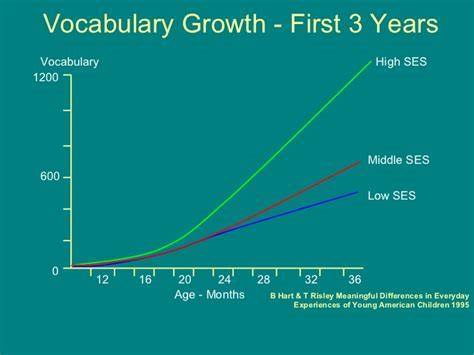

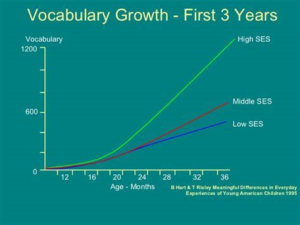

That argument has raged since researchers Betty Hart and Todd Risley did the original study. They published their findings in 1992 and included them in their 1995 book, Meaningful Differences in the Everyday Experience of Young American Children. Some people still don’t believe it.

In 2018, NPR suggested it was time to stop talking about the 30 million words gap, saying, “But did you know that the number comes from just one study, begun almost 40 years ago, with just 42 families? That some people argue it contained a built-in racial bias? Or that others, including the authors of a new study that calls itself a ‘failed replication,’ say it’s simply wrong?”

It’s true that no one has precisely duplicated the specifics of the study, but researchers have continued to produce results that support it. The website of the National Center for Clinical Infant Programs, zerotothree.org, extrapolates the word gap to be 32 million words by age four, saying, “Learning to read and write doesn’t start in kindergarten or first grade. Developing language and literacy skills begins at birth through everyday loving interactions, such as sharing books, telling stories, singing songs, and talking to one another.”

It’s likely that the 30 million words gap is much more fact than fiction. While sources don’t agree on the number of words, no one refutes the basic tenet that language exposure is a key factor in realizing a child’s academic potential.

That’s where it really gets interesting. The bulk of Suskind’s book isn’t about the word gap but the effects of early language exposure on the brain development of children from zero to three.

Language Exposure and Brain Development

This book and its conclusions are startling in several ways. First, is it true that the critical period in a child’s development is so early and so short? According to Suskind, it is. That is surprising enough, but there is more. The book suggests that early language is the foundation of brain development.

“By the age of three, the human brain, including its one hundred billion neurons, has completed about 85 percent of its physical growth, a significant part of the foundation for all thinking and learning.”

In the words of Nim Tottenham, a neuroscientist at the Child Mind Institute, “A rich language environment is like oxygen. It’s easy to take for granted until you see someone who isn’t getting enough.”

On its simplest level, Suskind calls the critical interaction between parent and child “Parent Talk.” On the first page of her book, Suskind states, “Parent talk is probably the most valuable resource in our world. No matter the language, the culture, the nuances of vocabulary, or the socioeconomic status, language is the element that helps develop the brain to its optimum potential.”

She refers to it as “the 3Ts.” A 2015 piece in USA Today laid the 3Ts out for their readers:

- Tune In: Notice what the child is focused on and talk about that. Respond when a child communicates – including when a baby cries or coos.

- Talk More: Narrate day to day routines, such as diaper changes and tooth brushing. Use details: “Let Mommy take off your diaper. Oh, so wet. And smell it. So stinky!”

- Take Turns: Keep the conversation going. Respond to your child’s sounds, gestures and, eventually, words – and give them time to respond to you. Ask lots of questions that require more than yes or no answers.

30 Million Words and The Early Catastrophe

In 2003, well after completing their original research, Hart and Risley, wrote a summary of their findings and experiences. It was published in American Educator, a publication of the American Federation of Teachers. The article has been archived by the Education Resources Information Center (ERIC). The abstract for the article reads as follows:

“By age 3, children from privileged families have heard 30 million more words than children from underprivileged families. Longitudinal data on 42 families examined what accounted for enormous differences in rates of vocabulary growth. Children turned out to be like their parents in stature, activity level, vocabulary resources, and language and interaction styles. Follow-up data indicated that the 3-year-old measures of accomplishment predicted third grade school achievement.”

They dubbed this phenomenon as “the early catastrophe,” because, according to Suskind, the reading level in third grade generally predicts the ultimate learning trajectory for all children.

In the American Educator article, Hart and Risley summarized their thoughts this way: “We learned from the longitudinal data that the problem of skill differences among children at the time of school entry is bigger, more intractable, and more important than we had thought. So much is happening to children during their first three years at home, at a time when they are especially malleable and uniquely dependent on the family for virtually all their experience, that by age 3, an intervention must address not just a lack of knowledge or skill, but an entire general approach to experience.”

Socioeconomic Status (SES) has long been considered one of the main factors in children’s academic achievement. Suskind’s book has prompted a new focus on the research of Hart and Risley as well as early language. Her own experience and developing programs may prove this conventional wisdom a lie. As she puts it: “Not having money in your pocket has never made a brain not grow. In the beginning, the food for the developing brain is language and interaction.”