We are failing our children in English education. This limits their command of the language, their communication skills, and their learning potential. Somehow, it has escaped our attention.

We used to understand that the fundamental features of public education were reading, writing, and arithmetic. These were and still are, after all, the minimum requirements for participation in society. A person can’t be expected to be self-sustaining, let alone a contributor to the general good, without these basics.

We supplemented these priorities with “citizenship” in various guises, teaching the simple virtues of honesty, courtesy, promptness, patriotism, and faith. In fact, in many of the original schools, these tenets took precedent with the youngest of students. In Japan, they still do.

Times change, however, and practices must also. But shouldn’t change be positive, productive? Instead, we are producing failure in our students in far greater numbers than success. We seem to refuse to learn from our mistakes. Our education gurus remain focused on the next new idea, when it might be time to take a step back. (If you’ve tried new math, you know what I mean. If you haven’t, this is a great example.)

How We Are Failing Our Children in English Fundamentals

We know our students can’t read, but we don’t change the way we teach reading. To compound our ineffectiveness, we have reduced the focus on basic language skills like penmanship, spelling, and grammar. What used to be simply labeled “English” has become “English Language Arts.”

If we were really teaching the “language arts,” we would focus on reading first, then spelling, grammar, vocabulary, and beyond. Teachers who balk at teaching boring, yet effective phonics can’t be expected to embrace the demands of grammar or vocabulary, let alone spelling. Yet, these are the building blocks of language fluency. And language fluency is the heart of efficient learning and effective communication.

Furthermore, there’s mounting scientific evidence that our failure to systematically build language skills adversely affects the development of executive function. We couldn’t be limiting our students’ potential more effectively if we tried.

Now We Are Expected to Reject Our English Heritage as Well as the Language Itself

I can remember when pundits started suggesting that reading would become a lost art because of the vast availability of video. That won’t happen. Unfortunately, what is happening is dilution of the traditional ELA curriculum in favor of more contemporary flavors.

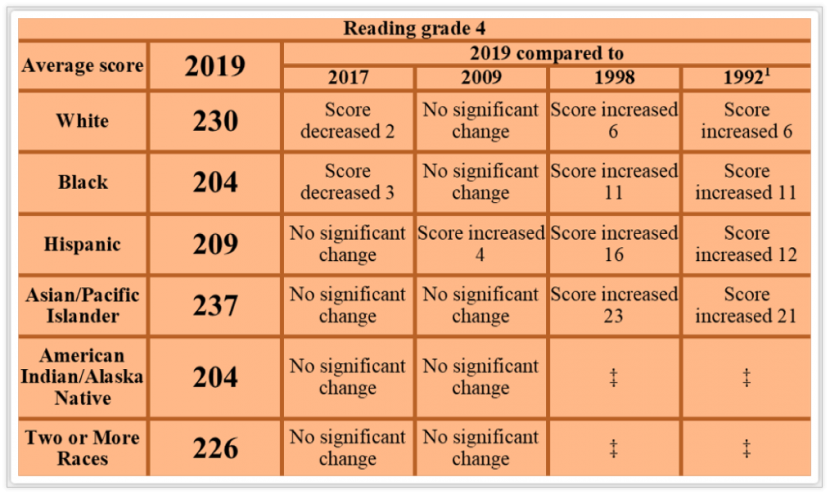

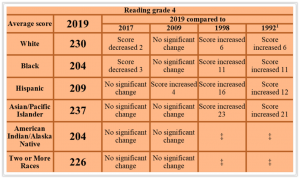

The education establishment has firmly planted its support in favor of bilingual education instead of requiring studies in English. This has cost our education system and our students plenty. You can confirm the results for yourself at NAEP.

In additions, there are plenty of voices calling for the removal of classics from the curriculum, particularly Shakespeare, for reasons that have nothing to do with the value of the works to an understanding of our language, our culture, or our history. As a teacher suggested recently in Teacher, he is too white and too male. He is undoubtedly too traditional and too binary.

Suddenly, all sources must march in lockstep with the current popular perspectives. We must reject the richness of the language and the characters in favor of current authors who are, though less elegant, much hipper. Using sexually explicit novels in middle school is fine so long as the gender roles are characterized correctly, but no Shakespeare!

We Are Reaping What We Sow

As multicultural education found a solid footing in the education system of the 1980s, we began letting go of our English focus. The requirements of a broader cultural background should mean having greater appreciation of other cultures without rejecting our own. However, that doesn’t appear to be the direction we are heading.

“Who controls the past controls the future.” That was George Orwell’s warning in his famous novel 1984. That message is falling on deaf ears. The removal of long-accepted English literature, not to mention the diminishment of the language itself, is not a positive force for the improvement of our students. Rather, it will redefine our history and weaken our potential.

Political correctness and social activism are welcome in the English classroom, where the focus on language can only help the flow of ideas. Certainly, Shakespeare and the other “old, white males” should be welcome as well.